The future is green, and at Van Iperen International, they’re also convinced of that fact. That’s why they are making the green switch. This journey has been running its course for a while, so let’s check-in to see how things are going. But what does making the green switch mean exactly? And what does it consist of in practice? Marc van Oers, innovations director at Van Iperen International, tells us more.

Sustainability

“By making the green switch, we want to bring our contribution to increasing sustainability of global agriculture, both greenhouse horticulture, and open field.” The company is active in fertilizer products and biostimulants for fertigation and foliar application. Their products are used on a wide range of crops, from grapes to potatoes, melon, pineapple, apple, strawberry, onion, mango, etc.

“We’re looking for methods and products that are chemically identical to the products currently used in high-tech agriculture and horticulture, but which are less taxing on the environment when it comes to their production.”

But making the green switch means also searching for new biostimulants, Marc continues. “We looked for crops that are efficient in nutrient and or water use efficiency. We grow them, extract their actives and apply those to other crops. The result is increased nutrient or water use efficiency and improved yield of the crops to which the extracts are applied”. The product range launched this year is called Plants for Plants.

The meeting of 2 worlds

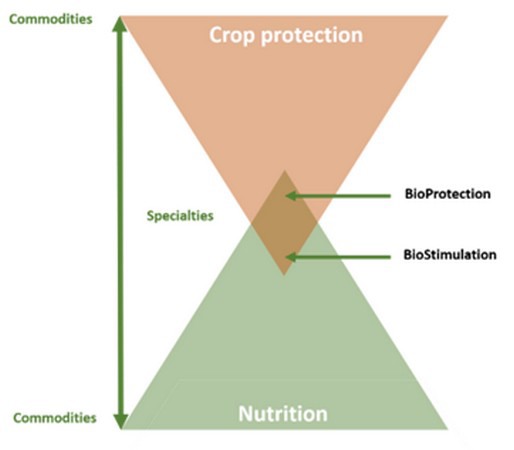

Van Iperen International has a number of innovation projects supporting their green switch journey. Marc explains: “In the past, we had the fertilizer segmentation starting from low-value products such as commodities and ending by the specialties, which back then were the trace elements. Today the trace elements are also seen as commodities and are replaced by biostimulants.” Next to that the crop protection product segmentation has also evolved over the years, creating new segments such as bioprotection. Where the worlds of fertilizers and crop protection used to be separate worlds, now there’s a meeting point between the biostimulants from the world of fertilizers and bioprotection products from the world of crop protection.”

Figure: the meeting of the Nutrition and Crop Protection worlds.

Partners

Development of those new products takes place at Van Iperen International, but also together with partners such as the Italian company Landlab, their partner for agronomic R&D. “In addition, we also have other partners, more often engineering companies. Examples are Pure Green Agriculture from the United States and Cinis from Sweden. They’ve got brilliant engineers who are capable of developing new technologies to produce known and existing fertilizers in a circular and far more sustainable way. They understand the technology, and we understand the market. Together we are capable of initiating a movement towards increased sustainability.”

Van Iperen International definitely has the necessary market knowledge for that. “We supply to more than 100 countries and have, next to our headquarters in the Netherlands, staff in Australia, Thailand, South Korea, Lebanon, Turkey, Serbia, Hungary, France, USA, and Costa Rica. We serve the local market, and in each of the countries we supply to, we have our own distributors.”

Potassium sulfate in Sweden

Marc gives details on two examples of GreenSwitch® projects running at Van Iperen International. The first one is with Cinis in Sweden. “We’ve been in talks with them for about four years now. They had the idea to produce potassium sulfate in a revolutionary way. Currently, nearly all potassium sulfate worldwide is produced according to the Mannheim process. That process requires temperatures of 600-700 degrees Celsius, which makes it a highly energetic process. The sulfuric acid that’s used comes from the crude oil industry, and Hydrogen Chloride as a side product of the Mannheim process is a headache for this industry. So there’s definitely room for improvement.”

At Cinis, they came up with a different process: more circular and consuming less energy. They work together with several companies in the north of Sweden, including Northvolt, a large player in the production of car batteries. “During the production of those batteries, a lot of sulfur is produced, which we can use as a residual stream. There’s also a large paper production industry in the north of Sweden. A lot of residue is produced by this industry currently discharged into the ocean. But that residue contains a lot of sulfur, so a method was conceived to remove the sulfur from that residue so that it doesn’t end up in the ocean anymore.”

The Swedish engineers also invented a method to turn sulfur into potassium sulfate at much lower temperatures, around 30 degrees Celsius. “So that’s circular and requires a lot less energy which in its turn is green energy. Together with Cinis, we’ll develop the market for that.”

Nitrogen

A second example: Five years ago, Van Iperen International got in contact with an American company, Pure Green Agriculture. “That company had the idea to use ammonium from manure to produce nitrate fertilizer. That way, you can produce potassium nitrate or nitric acid from manure.”

That principle has its origins in the water treatment industry – Pure Green Agriculture then took that idea and developed it further. “That’s why we’re now able to produce a clear solution of potassium nitrate at our plant in Hardenberg in the Netherlands called GreenSwitch® Original. The alternatives, a process invented by Haber, Bosch, and Ostwald in the early 20th century, is still the standard in the market. It requires a lot of energy because it’s done in a vacuum at high temperatures. In the new process, we strip ammonium from manure at biogas plants and turn this into nitrates using green gas. With the new process that we use, the CO2 footprint goes down by 80 percent, and it reduces the cost price of the production of green gas.”

Another advantage: when farmers apply ammonium from manure on their land now, 17 percent of the total Nitrogen applied is lost as Ammoniac, but there’s another way. “When you turn that Ammonium into Nitrate, which isn’t volatile, and use it in greenhouse horticulture or open field fertigation, that 17 percent turns into almost 0 percent. That way, we can also contribute significantly to combating the nitrogen problem.”

In the Netherlands, several pot plant growers have already started, like Hoogeveen Plants and Bunnik Plants. “Also, in plant nurseries and the cut flower industry, we have the first growers who already made the switch,” according to Marc. There is also an increasing interest in vegetable greenhouses, both inside the Netherlands as well as outside. Marc also sees opportunities for many other growers all over the world that are aiming to reduce their Carbon Footprint. First talks have been initiated in Australia and South Korea. Outside Europe, it’s also registered for organic agriculture.

For more information: Van Iperen

Van Iperen

www.vaniperen.com